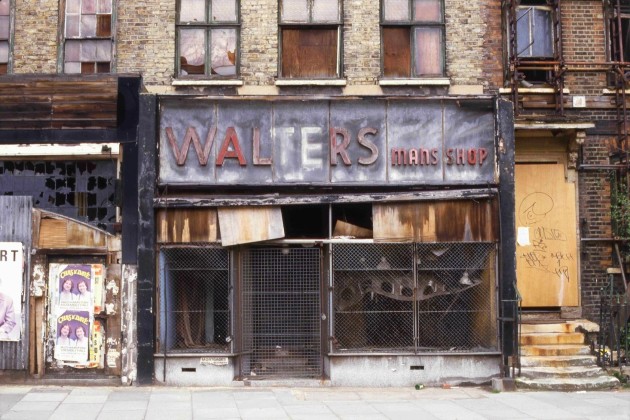

Ruinphobia, the New Ruins and the anti-ruination reflex – my newly published chapter is out

April 27, 2017 3 Comments

“The problems associated with empty properties are considerable. They attract vandalism and increase insecurity and fear. And this all reduces the value of surrounding businesses and homes. So the decision to leave a property empty is not just a private matter for the landlord. It affects us all.”

Mary Portas, The Portas Review: The Future of Our High Streets, 2011, p 35.

Portas here reveals that any discussion of transience and permanence in urban development engages deeply embedded cultural assumptions about utility and progress. I explore the origins and effects of this anxiety in a contribution to a recently published collection of essays on the theme of temporary re-uses of vacant urban property. In my chapter I show how an underlying ruinphobia quitely but powerfully shapes the fate of abandoned buildings, regardless of how some might more loudly valorise them through a ruinphiliac (or ruin lusty) gaze.

In my chapter I place recent (largely ruinphiliac) ruin studies scholarship in the arts and humanities alongside insights from both critical urban studies and the more professionally focused concerns of real estate practitioners in order to see what happens when ruinphobia and ruinphilia try to inhabit the same space. As a taster here’s a snippet, in which I set up the juxtaposition by taking Edgar Allan Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher off for a walk in a direction he didn’t intend:

“The ruin is a provocative mix of time and matter – it shows us simultaneously the longevity and the ephemeral nature of both buildings and their uses. It also holds a mirror up to our relationship with their constituent matter, destabilising our perception of and reaction to the building as a whole, and the building as an assemblage. It is also paradoxically both a lawless prospect – and yet strangely of the law. To pursue these points let us dwell for a moment at the threshold of The House of Usher. Let us imagine that we are standing there with Edgar Allan Poe’s unidentified narrator as he looks upon the bleak vista, scrutinising the building before him and searching out its sublime import:

“more narrowly the real aspect of the building. Its principal feature seemed to be that of an excessive antiquity […] yet all of this was apart from any extraordinary dilapidation. No portion of the masonry had fallen; and there appeared to be a wild inconsistency between its still perfect adaptation of parts and, the crumbling condition of the individual stones” (Poe, 2003, p 94)

But what if we re-contextualise the scene, replacing Poe’s intimated ruinphiliac frisson with a workaday ruinphobia? Then – perhaps – our unidentified narrator becomes the occupant’s tax adviser, come to advise the decrepit titular owner upon demolition or a creative ruination ruse to avoid Business Rates. Perhaps he has come to disassemble the building, totting up as he looks on, how many stone blocks, lead pipes and copper cupolas the House of Usher will yield when levelled. Perhaps he has come from the local council and will shortly serve legal notice upon the owner, commanding corrective works under the Building Act 1984. Perhaps he has come from next door, alleging recourse against Usher under the common law principles of Private Nuisance, for damage sustained by his own property caused by this decaying structure. Perhaps he is a local councillor concerned about the adverse effects of this dereliction upon the amenity of the neighbourhood, and is contemplating the scene with a view to producing a report to his Council’s cabinet in favour of action being ordered under Section 215 Town & Country Planning Act 1990. Perhaps he is the local crime prevention officer attending to warn the owner that the degenerating condition of his place is a magnet to crime. Perhaps he is an insurance broker, steeling his nerve before breaking the news to his client that policy premiums are now prohibitively expensive, on account of the recent decline of this once stately house.

The Fall of the House of Usher is fiction, it is just a story. It is presented as an entertainment – predicated on the assumption that there is a willing audience for tales that summon the prospect of standing, contemplating the degeneration of a ruinous building, and getting some unsettling thrill from vicariously doing so, whilst reading the story in the safety of our own warm, cosy and familiar homes. But, much as we might enjoy TV crime shows and their grizzly exceptionality, we do so only from a safe distance: we only want ruination in controllable amounts, too much or its occurrence at a time and place not of our choosing is cause for a different type of unsettling – one that calls for action, intervention and eradication of the ruin.”

The edited collection in which my essay appears is Transience & Change in Urban Development (ed. John Henneberry, Wiley-Blackwell, 2017), and its rather pricey (more details here). But there’s an early version of what eventually became my chapter here, worked up with some initial help from my SHU colleague Jill Dickinson. The book’s chapters derive from an international EU funded workshop convened by John Henneberry in January 2015.

Image credit:

Abandoned shop front, 1988: https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/414190496956316175/

Reblogged this on Installing (Social) Order and commented:

“Ruinphobia” and the anti-ruination reflex — worth a look.

I look forward to reading the whole chapter Luke! Looks great.

Pingback: Ruinphobia, the New Ruins and the anti-ruination reflex – my newly published chapter is out | deer hunting