CALL FOR PAPERS – ‘law and geography’ (a special issue of the International Journal of Law in the Built Environment)

October 24, 2013 1 Comment

‘Law and geography’

A special issue of the International Journal of Law in the Built Environment

Guest Issue editors:

Luke Bennett, Department of the Natural & Built Environment, Sheffield Hallam University; &

Professor Antonia Layard, Birmingham Law School, University of Birmingham

Call for papers

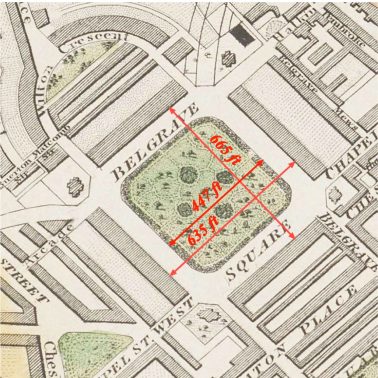

‘What would be a nuisance in Belgrave Square would not necessarily be so in Bermondsey’

per Thesiger LJ, in Sturgess –v- Bridgeman (1879) 11 ChD 852

By this CFP we invite submission of high quality papers written by legal scholars, urbanists, geographers and social scientists that explore law’s place amidst the spatiality and materiality of the built environment. Our aim is to gather a collection of papers which can bridge the ‘critical’ and ’embodied’ practical aspects of making and managing built environments. We seek to do this by setting critical legal geography perspectives alongside practice oriented built environment legal scholarship, in order to explore potential synergies and creative tensions that may arise from this juxtaposition.

In keeping with IJLBE’s broad remit, papers can be empirical, doctrinal and/or theoretically based and can explore the themes suited to this CFP in any jurisdiction around the world (please note that submissions must be written in English).

We are seeking articles which engage the ways in which law is at work in the built environment and do not wish to be overly prescriptive. But, indicatively, questions that submitted papers might address include:

– How does law contribute to the making and controlling of the built environment at multiple scales?: ranging perhaps from the micro-world of design standards for building components upward and outward through law’s shaping influence over rooms, floors, buildings, terraces, wards, boroughs, cities, regions, nationalities and globally.

– What is law’s relationship with space, place and physical structures in the built environment – and in particular how are objects framed by law (for example by how objects of concern are defined in built environment regulatory laws; or in judicial attempts to develop a ‘complex structure theory’ as a way of conceptualising – and litigating – building defects)?

– How can legal processes of built environment place making be critiqued through the lenses of critical geography and progressive urbanism? And in doing so, what are the implications for built environment scholarship and its concern with professional practice?

– What are the dangers of conflating law and geography? What methodological problems will be encountered? What claims to knowledge and validity can such hybrid analysis of law and geography claim?

– What role do judicial and other spatio-material imaginaries (images of place and things) play in the adjudication of cases concerning contested land use and/or the conduct of processes that have as their aim the legally shaped ordering of space and/or physical things?

About legal geography

This call for papers arises out of a double session convened by the guest editors at the Royal Geographical Society’s 2014 Annual Conference. It is part of an initiative seeking to raise the profile of legal geography as a hybrid area of scholarship within the UK and to connect with the established Legal Geographers active – in particular – in North America and Australia.

Legal geography is an emerging discipline, located both within geography and with law and society studies. It draws on legal and geographical techniques and concepts to understand ‘the role and impact that space and place have on the differential and discursive construction of law and how legal norms and practices construct space and places’ (Blomley 1993, 63). The central assumption is one of reflexivity: that law constructs space and place and that space and place construct law (both in books and ‘in action’).

While some legal geography research is profoundly theoretical, other more doctrinal and empirical legal research is often highly situated. It is located (to give just a very few examples) on the streets (Blomley, 2011; Valverde 2012); within gated or common property (Blandy, 2006, 2010); shopping centres (Layard 2010); on the boundary (Kedar 2002; Braverman, 2009); in local communities constructed through racial legal geographies (Ford, 1999; Delaney 1998); in a field next to a pub (Bennett, 2011) or in an eruv (Cooper, 1998).

It is perhaps at this situated scale that legal geography comes closest to scholarship concerned with the professional practice aspects of the built environment and its law. It is in this field (as this journal reflects) that the law is encountered as a managerialist tool, it is concerned with ways of ordering and managing the design, construction, ownership, use and removal of places, their physical structures and also of their human inhabitants. Here applicable laws seek to frame these material things in order to know and thereby control them – and their actions – across time and space. Law in the built environment thus has at its heart a practical concern with the governability of things. Perhaps a fusion of legal geography and built environment legal scholarship can open up insightful routes to the understanding, refinement and critique of the processes by which law is translated (Latour 2005) into buildings, streets and the urban landscape.

How to submit a paper

The deadline for submission of papers for consideration is 23 January 2014. Papers should be submitted via the publisher’s on-line submission point: http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ijlbe.

Full details of the Journal’s instructions to authors regarding words limits, citation, layout and writing style are available here:

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/products/journals/author_guidelines.htm?id=ijlbe

Submitted manuscripts can only be considered if they adhere to these procedures and instructions.

The editors are very happy to correspond via email with potential contributors prior to the submission deadline regarding queries related to this CFP and/or the ‘fit’ of any paper or proposal.

Following peer review selected papers will be published in the ‘law and geography’ themed issued of the journal (Volume 7, Issue 2), in July 2015. The selected papers will also be advance published on-line via the publisher’s EarlyCite facility, in (we estimate) Autumn 2014.

About the journal

The International Journal of Law in the Built Environment was launched in 2009 and is published by Emerald. It provides a vehicle for the publication of high quality legal, socio-legal and related scholarship in the context of the design, construction, management and use of the built environment. It publishes up-to-date and original legal research contributions for the benefit of scholars, policy makers and practitioners in these areas, including those operating in the fields of legal practice, housing, planning, architecture, surveying, construction management, real estate and property management.

A specific aim of this special edition is to consider how the journal can connect its concerns with wider academic communities sharing an interest in urbanism, place making and the building of environments.

Further details (including sample articles) are available here:

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/products/journals/journals.htm?id=ijlbe

Image source: http://londonsquares.net/4-squares/2-belgrave-square/