Casual eschatology, or the banality of Ethel

September 10, 2013 Leave a comment

Ethel stoops half way along the corridor, brushing against Brendan’s jumper as she folds her torso towards the ground. “They told her it would be a few weeks, but four months is ridiculous” she says looking across to Karen as she steadies herself against the wall and picks at the leaflet she has just dropped, her fingers chase-pushing it across the dull, battleship grey linoleum.

“I told her when I saw her that she should be more assertive; stand up for herself. I wouldn’t put up with it, I really wouldn’t!”

On the wall to her left, the fallout charts hang in wilting order, tiny traces of rust seeping from drawing pins, paper clips and treasury tags that clamped them in archival congress for many years. Brendan glances across at the doorway ahead, strange word he thinks – ‘geiger’, strange too that this place should be the UK’s geiger counter museum. He expects stuttered clicking, a sound museum of racked and labelled beeps, but finds only shelves of dull metal boxes, the tethers of chunky rubberised wands. They remind him of car batteries, and of a comptometer that he used when he worked in purchasing before moving on into sales.

Karen is speaking now. “Oh look Ethel, just like the ones we used at Taylor’s”. She’s looking across at the row of computer terminals – one short evolution on from telex terminals. The attendant chairs are coated in stretch fabric, a vivid floral camouflage of orange, mustard and brown. On the wall beyond a bank of electronics: switches, lights, etch stencilled labels. Adjacent stands a tea trolley, cups stacked ready for use beside the ample looking calorifier.

They stand and stare, Ethel finds herself to be caressing the rope barrier holding them apart from this secretarial array. “Like an office crime scene” she idly remarks under her breath and she recoils from the fibrous barrier, and her strange desire to carry on stroking it. They stroll back into the corridor and wander down toward the slim door at the far end. There is a large sign affixed to the door, warning them of what lies beyond. Intrigued they step inside. The room is small, and illuminated by a single unshaded red bulb. There are three utility chairs. They take the opportunity to sit and rest themselves. There is a ventilation duct high up on one of the walls. From it comes a rattling sound, like a steady flow of wind blowing through, but there is no draught.

Then the light starts to flicker, then the room falls silent. They sit and stare at each other, then Karen speaks. “shall we go to the cafe now? I’m, getting thirsty”. Ethel and Brendan signal agreement by rising from the chairs, only to be jolted back onto them by a sudden klaxon, reverberating forcefully within this confined space. Shocked into supplication, they sit as the siren volume and insistence appears to swell around them. Then the room starts to shake, the light flashes wildly, then stillness and silence, and then the sound of rubble tumbling down into the ventilation duct.

Eventually the movement stops, then the flickering light and the whistling of that wind completes the cycle. They compose themselves and leave the room. The light of the corridor is now painfully bright until their eyes adjust.

The route to the cafe takes them through the bomb room, warheads to touch – that thick paint, chunky metal essence of something made carefully to order; the bespoke chic of destruction. And over on the walls the photographs of the wranglers of these small herds, proud moustachioed men looking up from an era before manliness became shaven headed.

And then into the cafe. The froth-throb of the coffee machine, the ‘tink’ of chrome, stainless steel and plastic chairs going about their business. In the corner a cold drinks machine crackles and from the kitchen drifts the strain of indistinct light music. Our companions sit and refresh themselves. Brendan goes to the counter and flicks through the stock of leaflets for Cheshire’s other attractions. “Where to next weekend?” he calls limply across to Ethel and Karen, half rhetorically.

Meanwhile, beyond the sturdy blast proof walls and doors, the flat plain of rural south Cheshire rolls onward in an anonymous clay ridden green-brown sea . And in the adjacent fields the cows beat the passage of time – sometimes sitting, mostly standing – watching cars occasionally come and go. They dwell here, come winter, come summer. Swishing flies and munching grass, sometimes drawn to the flank walls of this square grey building because it shelters them from the bitter winds blowing across the plain, sometimes catching warmth from the slow thermal release of this bulwark mass.

What was that?

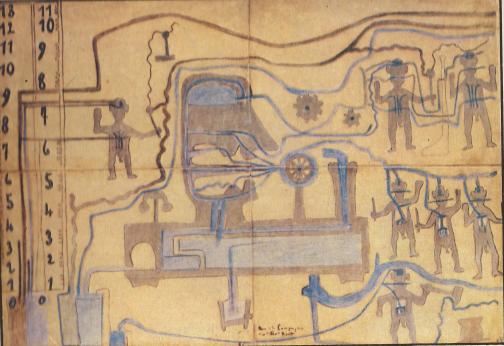

I wanted to write an anti-account, one that backgrounds the Hack Green bunker, and gives something of the sense of ambivalence I felt (and witnessed in others) as we strolled around this former ‘Regional Seat of Government’ civil defence bunker (now a museum). Intentionally there’s no history of place or purpose written here. I’ve touched on that stuff elsewhere. No, as I sat today and thought about my visit three years ago one quiet Sunday afternoon, it was the ubiquity of this place and people’s behaviour within it that came to mind the most. I’ve used other photos from my visit in other published outputs, but it’s these banal ones – ones that deny this bunker its potency – that I wanted to let breathe here.

[This is New Uses For Old Bunkers #35]